Introduction

This Akava Works review series analyses immigration issues by focusing on the number of residence permits granted in Finland. The emphasis of the analysis is on work permits for highly skilled workers, which includes specialists and researchers. The primary message from the previous two reviews remains largely unchanged: there are now more residence permits being issued for Finland than in earlier years. Furthermore, in the previous reviews, it was noted that Russia’s war on Ukraine has significantly increased the number of work permits granted to Russians.

As the source of its data, the review draws on statistics from the Finnish Immigration Service and specifically concerns first residence permits. Neither extended permits or permanent permits are included in this review. To gain a better understanding of the volume of migration into Finland, it makes more sense to focus on first residence permits, since the applicants do not, generally speaking, reside in Finland.

It is also important to note that this review series only focuses on the type of immigration that requires a residence permit. Nationals for EU/EEA countries or Switzerland are not required to have a residence permit, since they are granted free movement to Finland. At the same time, this means that statistics on the immigration reasons for nationals from these countries are not compiled. For that reason, it is impossible to assess on an annual, let alone quarterly, basis the volume of work-based immigration into Finland from countries enjoying freedom of movement.

As per its name, the residence permit allows for a stay of longer than 90 days in Finland. The permit is primarily sought for work, studies or family reasons. A residence permit is not necessary for anyone who is a national of another EU Member State, Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Switzerland. Nationals from these countries are granted free movement, but must register their right of residence in Finland if they intend to stay here for more than three months. In addition to residence permits and freedom of movement, the third means of entry into Finland is for international protection.

This review focuses only on those applying for first residence permits. Persons applying for a residence permit in Finland for the first time will apply for a first residence permit. When the first residence permit is about to expire, it is possible to stay in Finland by applying for an extended or permanent residence permit.

The number of granted residence permits remains at record levels

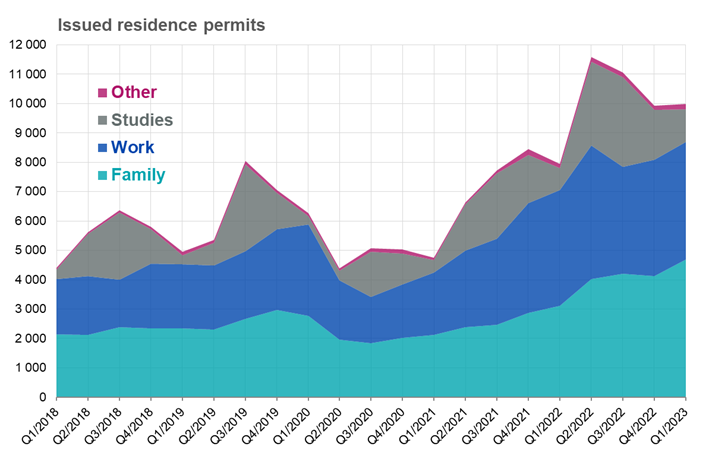

In the first quarter of 2023, January–March, a total of 9,989 residence permits were granted (Figure 1). Of these, 4,681 were granted for family reasons, 4,007 on the basis of employment, 1,119 for studies and 182 for other reasons. The number of granted residence permits has clearly been rising since the COVID-19 pandemic has begun to recede. If students are excluded, a new record in the number of permits was once again achieved in the first quarter of this year. Typically, the number of permits issued to students is highest during the third quarter of the year, at the end of summer and beginning of autumn.

Altogether over the past 12 months, a total of 42,545 first residence permits were granted in Finland. Of these, 16,149 were granted on the basis of employment, 17,033 for family reasons, 8,742 for studies and 618 for other reasons. Other reasons may include, for example, work as an au pair, adoption, jobseeking in Finland and committed relationships.

Figure 1: Granted work permits by applicant group (first resident permits) Source: Finnish Immigration Service

A residence permit for an employed person is granted in two phases. The TE Office makes a partial decision on the employee’s residence permit application and the Finnish Immigration Service makes the final decision. The partial decision of the TE Office is based on an overall assessment, which includes assessing the applicant’s income level and the employer’s ability to meet the mandatory obligations set out for employers. Another essential aspect of the TE Office decision is an assessment as to whether suitable labour from within the Finnish and EU/EEA labour markets would be available within a reasonable period of time to fill the vacancy in question.

Work permits for specialists are subject to stringent screening. First of all, the duties of a specialist require a high level of expertise. One typical example of this type of expertise is that required for work duties in the ICT sector. Additionally, applicants are usually required to hold a higher education degree unless they can present other specific grounds for immigration. In 2023, applicants were also required to receive a minimum monthly salary of EUR 3,473 or, for EU Blue Card specialists, EUR 5,209. Unlike those carrying out jobs with lower skill requirements, specialists are not required to apply for a partial decision from the TE Office.

Work permits granted on the basis of scientific research are granted to persons looking to conduct research in Finland. Additionally, these work permits are granted to persons who come to Finland after completing a Master’s Degree for the purpose of pursuing a licentiate or doctoral degree. In other words, a person looking to complete a further degree in Finland should apply for a residence permit on the basis of work, not studies. As is the case for specialists, researchers do not need to apply for a partial decision from the TE Office.

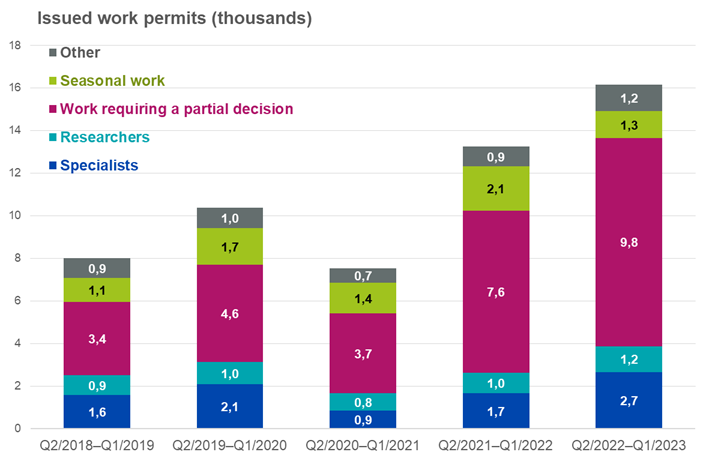

The majority of work permits are granted for worker occupations

The majority of residence permits for employed applicants, work permits, require a partial decision prior to final processing. These types of work permits require a favourable statement based on the overall assessment of the TE Office and are primarily granted to those in worker occupations. Over the previous 12 months, altogether 9,760 of such permits were granted, representing 60 per cent of all work permits. The number has increased notably in comparison to the period prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, when, typically, 3,000–5,000 work permits were granted each year.

Roughly speaking, the work-based immigration of highly skilled workers refers to specialists and researchers who, as a group, accounted for almost a quarter of all work permits granted over the past 12 months. Last year, a total of 2,655 work permits were granted to specialists and 1,225 to researchers, which is more than any earlier review period. The increase in the number of permits has, however, been more moderate in recent years than the number for those in worker occupations. Considering all work permit recipients, the share of those who are highly skilled immigrants was higher prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2: Granted work permits by applicant group (first resident permits) Source: Finnish Immigration Service

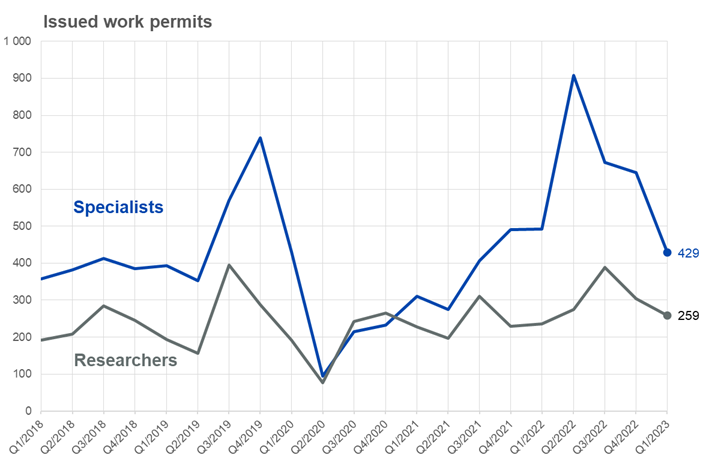

The number of permits issued to specialists is in decline

Figure 3 presents the number of residence permits granted to specialists and researchers by quarter. The number of work permits granted to specialists rose significantly in the second quarter of 2022, but then decreased dramatically towards 2023. In the first quarter of this year, a total of 429 permits were granted, which is less than half of the peak in 2022. Only the COVID-19 pandemic has previously caused a similar decline in the number of permits for specialists as seen during the review period. Work permits for researchers have also decreased from their peak in 2022, even though the decrease was clearly more moderate than that of specialists. Work permits granted to researchers are also affected by natural seasonal fluctuations in the same way as residence permits for students (Figure 1). This fluctuation partially, if not fully, explains the decline in permit numbers.

Figure 3: Work permits issued to specialists and researchers by quarter (first residence permits). Source: Finnish Immigration Service

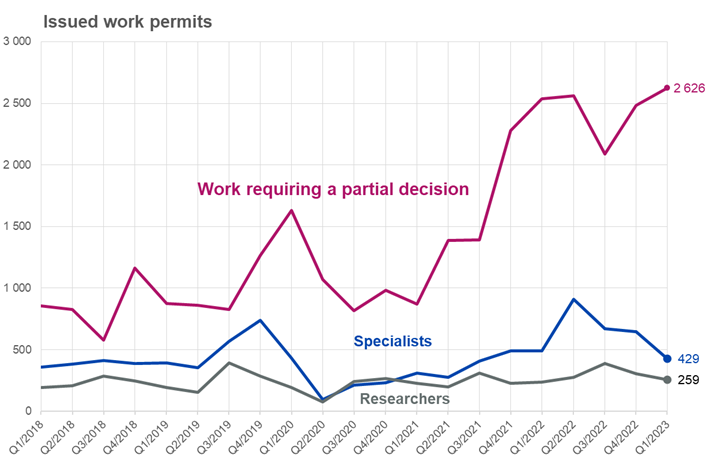

The previously mentioned dramatic drop in the number of work permits on the quarterly level appears to exclusively concern specialists. This becomes clear when we expand the review to include residence permits based on work that requires a partial decision (Figure 4). This group, which is largely comprised of applicants in worker occupations, does not show the same type of decline in work permits as that concerning specialists. On the contrary, during the first quarter of 2023, this group was granted 2,626 work permits, which is the highest number during the review period in question.

Figure 4: Work permits for specialists, researchers and employees engaged in work requiring a partial decision by quarter (first residence permits). Source: Finnish Immigration Service

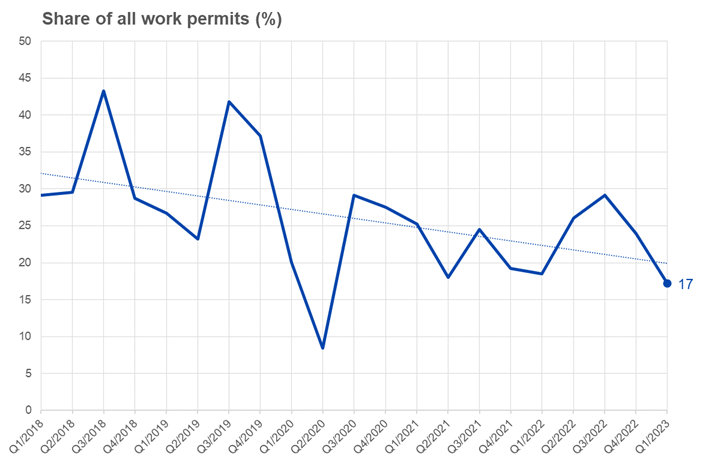

A visual inspection of Figure 4 shows that the disparity between the number of work permits granted for those in worker occupations and in highly skilled occupations has increased over time. For example, the quarterly volume of work permits granted on the basis of work requiring a partial decision was approximately 200–500 higher than for specialists. During the previous two years, the corresponding difference had increased already by about 1,000–2,100 permits per quarter. The share of all work permits granted to those in highly skilled professions, such as specialists and researchers, has already been decreasing for some years (Figure 5). During the first quarter of 2023, the aforementioned share was 17 %, which is the second lowest figure since early 2018.

Figure 5: Share of work permits granted to specialists and researchers of all work permits granted by quarter (first residence permits). The trend is indicated by the dashed line. Source: Finnish Immigration Service

Simple explanation for the decline in permits

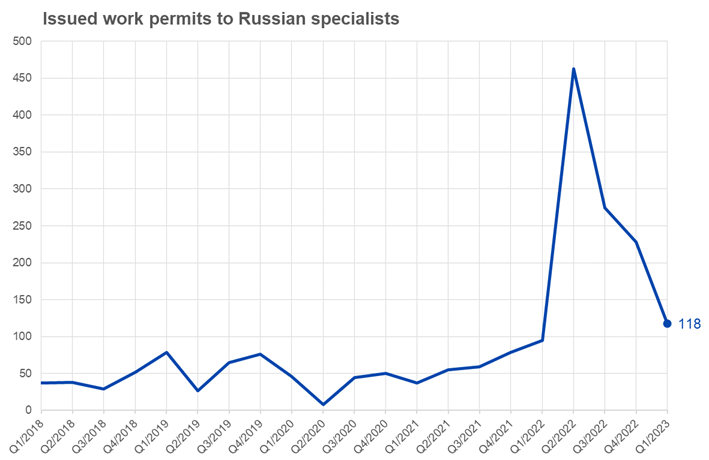

What then explains the fact that clearly fewer specialists have immigrated to Finland for work over recent months in comparison to earlier periods? In this case, there is only one factor that explains this: the migration of Russians. As a result of Russia’s war on Ukraine, there was an enormous increase in the number of permits granted to Russian specialists during the second quarter of 2022 (Figure 6). This growth spike appears, however, to have been only a temporary phenomenon. At the highest point last year, Russian specialists were granted 463 residence permits for the quarter, but during the first quarter of this year, that figure had already dropped to 118. Prior to 2022, approximately 50 work permits were typically granted to Russian specialists in any quarter. It may be that we will once again see a return to this stable level in the near future.

Figure 6: Work permits granted to Russian specialists by quarter (first residence permits). Source: Finnish Immigration Service

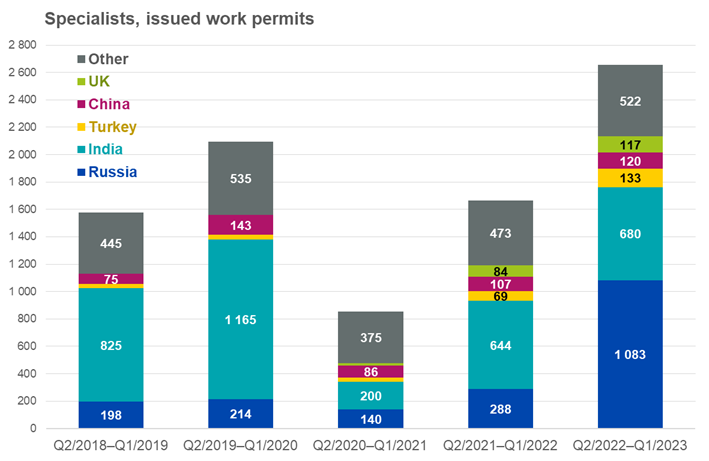

The number of work permits issued to Russian specialists dropped significantly as we neared the start of 2023, but on the other hand, the permit volume for last year reached an exceptionally high level. As a result, the number of residence permits granted to Russians over the past 12 months was at a record high (Figure 7). On the whole, it is practically due to Russian immigration alone that a record number of permits were issued to specialists over the past year. If Russians had been granted the usual 200–300 work permits during the last year, the overall number of issued residence permits for specialists would have been around 1,800. This level would have been slightly larger than one year earlier, but less than the highest volume seen prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (Q2/2019–Q1/2020).

Indian applicants have traditionally been the largest applicant group among specialists, but their numbers have still not recovered from the decline caused by the pandemic. Still prior to the pandemic (Q2/2019–Q1/2020), a total of 1,165 work permits were granted to Indian specialists, which is a staggering 70 per cent more than during the previous year. After India and Russia, the most popular countries of departure in terms of specialists include Turkey, China and the United Kingdom. Over the past 12 months, specialists from these countries were each granted approximately the same number of work permits, which is around 120–130.

Figure 7: Work permits granted to specialists by nationality (first residence permits). Source: Finnish Immigration Service

Wider diversity in nationalities among researchers

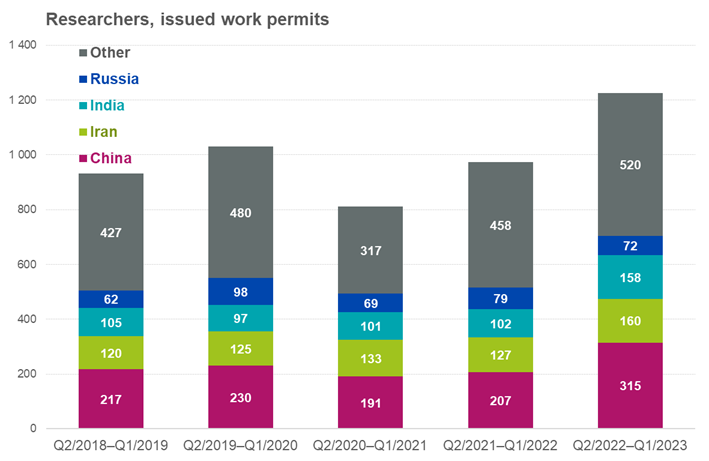

The number of work permits granted to researchers have fluctuated less over recent year than they have for specialists. While work permits for specialists decreased by 59 per cent from the previous year during the worst COVID-19 pandemic period of Q2/2020-Q1/2021, the corresponding drop for researchers was only 21 per cent. Furthermore, there is more diversity in terms of the nationalities among researchers (Figure 8). In other words, the lion’s share of the migration of researchers did not originate from only one or two countries of departure, as was the case for specialists. From the start of 2018, the top four countries of departure for researchers have been the same, from the largest to the smallest: China, Iran, India and Russia.

As was the case with specialists, researchers were also granted a record number of residence permits during the previous 12 months. As opposed to specialists, the increase in the number of Russians did not, however, explain the increased migration of researchers. On the contrary, Russia’s war on Ukraine did little to increase, let alone decrease, the number of Russian researchers seeking to enter Finland. Over the past year, the growth in the number of work permits was primarily due to the migration of Chinese, Indian and Iranian researchers. The number of work permits for Chinese and Indian immigrants increased as much as over 50 per cent from the previous year.

Figure 8: Work permits granted to researchers by nationality (first residence permits). Source: Finnish Immigration Service

Large sectoral and regional concentrations concerning the workplaces of specialists

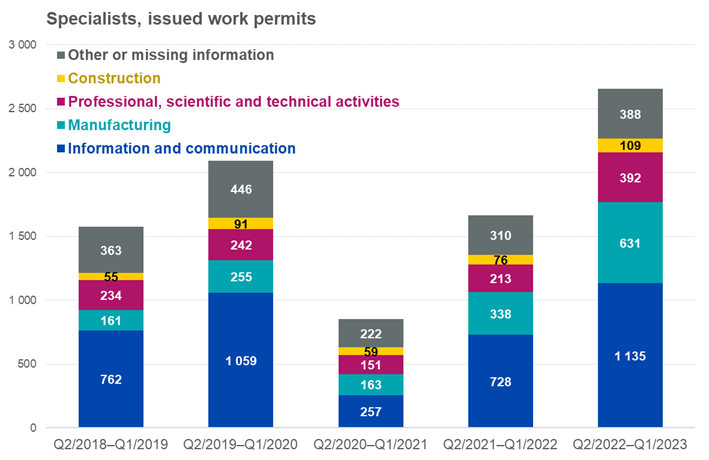

As seen in earlier reviews, only a few sectors employ the majority of specialists (Figure 9). The information and communications technology (ICT) sector is the largest employer of specialists. During last year, altogether 1,135 work permits were issued in the ICT sector, which is not, on the other hand, significantly more than just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit. By contrast, an increasing number of specialists from foreign countries are applying for jobs in the manufacturing sector in Finland. Over the past 12 months, a total of 631 work permits were granted to specialists in the manufacturing sector, while the corresponding level in earlier years was 160–340. The Professional, scientific and technical activities sector is also increasingly employing specialists to some extent.

Figure 9: Work permits granted to specialists by field (first residence permits). Source: Finnish Immigration Service

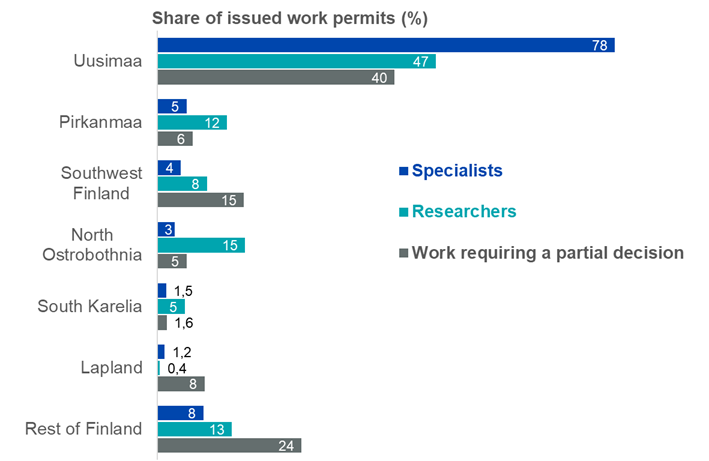

For those specialists who received work permits and for whom regional data was available, nearly 80 per cent were employed in the region of Uusimaa at some point during the past 12 months (Figure 10). Slightly more than 10 per cent of specialists applied for work in the regions of Pirkanmaa, Southwest Finland or Northern Ostrobothnia. The geographic dispersion of researchers is clearly greater than that of specialists, even though nearly half of them were employed in Uusimaa. The greater dispersion can likely be explained by the fact that Finland’s network of higher education and research institutes are spread throughout the country. Regions other than Uusimaa that employed an especially high number of researchers included the aforementioned Northern Ostrobothnia (15 per cent), Pirkanmaa (12 per cent) and Southwest Finland (8 per cent).

In comparison to highly skilled professions, the geographical dispersion of those hired to worker occupations (work requiring a partial decision) is greater. Over the past 12 months, Uusimaa employed 40 per cent of them. For worker occupations, Lapland is clearly overrepresented (8 per cent), considering that only three per cent of Finland’s population lives in this region. This exceptional observation can likely be explained by the labour shortage that the tourism and catering sector has endured for some time already and which is a significant employer in Lapland.

Figure 10: Work permits by region Q2/2022-Q1/2023 (first residence permits). Includes those persons for whom regional data is available. The regional data is missing for 136 specialists (5% of the figures), 443 researchers (36% of the figures) and 1,539 of those employees engaged in work requiring a partial decision (16% of the figures). Source: Finnish Immigration Service

Summary

The primary observation in this review, in terms of the number of residence permits, is largely the same as in earlier review for this series. The number of residence permits granted in Finland has seen an increasing trend following the worst COIVD-19 pandemic, and they are currently being granted at a record number.

At the end of the previous review (in Finnish), I estimated that as Russian migration flows slow in the future, we may see a dip in the number of work permits for specialists. In a short review period of only one quarter, this dip was clearly realised early this year. In terms of the longer review period of 12 months, no decline shows quite yet and, on the contrary, more work permits were granted to specialists during the year than ever before. This record, however, is exclusively due to Russia’s war on Ukraine and the resulting significant, but likely temporary, immigration peak for Russian specialists in 2022. Also during the 12 month review period, we will likely still see a drop in the number of specialists immigrating to Finland this year.

An especially interesting aspect of the aforementioned decline in the number of work permits is that it concerns only specialists. During January-March of this year, there was even a new record high for work permits granted to those in worker occupations. At the same time, the number of permits for specialists dropped by more than 50 per cent from the peak of last year. The different trends in the numbers of work permits granted on different grounds will result in a decrease in the proportion of highly skilled immigration of all work-based immigration. This is not, as such, a completely new phenomenon, as the trend of the above-mentioned share has been declining at least since 2018.

Lisätietoja:

Tomi Husa

asiantuntija

tomi.husa@akava.fi

+358 44 3664 011

Vesa Saarinen

Tuottaja

vesa.saarinen@akava.fi

050 3723473